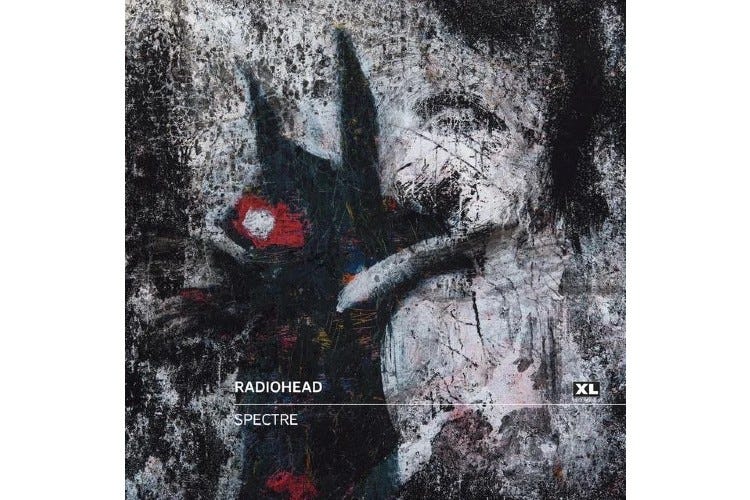

The World is Wrong, Volume 3: Radiohead's "Spectre"

The suits just didn’t get it, man

In the first two entries in this series — the O’Brien/Smigel sitcom Lookwell and divisive the Coen brothers film The Hudsucker Proxy — the corporate suits behind the project are surprising non-villains. Smigel and O’Brien explicitly said that the studio “got it”, and The Hudsucker Proxy is the rare case of a studio telling successful indie filmmakers “let’s see what you can do with a bigger budget” (before saying “well that didn’t work — your next three movies will have smaller budgets than a home movie of a toddler’s dance recital”). Artistically-brilliant-but-commercially-dodgy stuff is supposed to fall into obscurity due to cackling corporate suits who are blind to the genius in front of them. The situation with Lookwell and Hudsucker is more like that State sketch where the teenager wants to rebel but his dad is too cool.

Today’s entry — Radiohead’s “Spectre”, the James Bond theme that wasn’t — more closely follows the pattern you might expect. An art rock band got involved with a corporate mega-project. They made a song that might have elevated the whole project, but the suits got cold feet, feared they might alienate normies with avant garde arthouse bullshit, and opted for a work that could be called “Carson Daly-esque”, meaning: Its main trait is that it’s unobjectionable.

The connection between Britain’s mopiest rock quintette and a movie franchise known for delivering adventure, assassinations, and ass – not necessarily in that order – seems to have begun when the band and the director realized that each is a fan of the other. Radiohead’s Thom Yorke is a Bond fan, and director Sam Mendes – who was at the helm of the 2015 film that ended up being Spectre – is a Radiohead fan. And, as everyone in entertainment knows: You should always guilt your fans and friends into making stuff for you for cheap. Always leverage your relationships, always make people work for less than their usual fee out of a sense of obligation/guilt. This is especially true if you’re dealing with people who have artistic credibility, like Radiohead, because arthouse types typically find it uncouth to say “Motherfucker you need to pay me.”

When Mendes reached out to Radiohead, they informed him that they had already written a Bond theme: A song called “Man Of War”, which they recorded in the ‘90s but didn’t release. Now, if I’m Mendes, I might have smelled bullshit; it’s easy for a band to say “Oh, wow, what a coincidence – we already made the thing you wanted us to make! It’ll be the perfect Bond theme, it’s called ‘Get Yo’Self Dronk and Shake That B’donk’.” But “Man O’ War” does actually appear to be written for 007 – one of the lyrics is “I wish you could see me dressed for the kill”. Years later, it made it onto an album – this is it:

But here’s where art and commerce started to be at loggerheads: “Man O’ War” wasn’t eligible for an Oscar because it wasn’t written specifically for Spectre. And movie studios care about that stuff; Oscar buzz boosts visibility, plus there’s a chance that you’ll get a little gold statue that you can look at any time you feel like you wasted your life. So, in the interest of goosing the buzz for that plucky, obscure indie film franchise known as “the James Bond movies” (I hope I’m spelling that right), Radiohead would need to write a new song if they wanted to be considered.

So, they did! And in an incredible coincidence, it was also called “Spectre”. Here it is, played over the Spectre credits, as enjoyed by audiences in alternate timelines that are better than ours:

If you ask me, that’s a really good song (ed note: Nobody has asked me, nor will they, nor should they). Why didn’t it become the Bond theme? Two reasons have been given.

The first is that the song arrived too late to be in the movie. This strikes me as an Olympus Mons-sized pile of bullshit. Blockbuster Hollywood movies involve galactic sums of money, so every element that gives their film even an infinitesimally better chance of success is aggressively pursued – see, for example, the studio’s insistence that the song be eligible for an Oscar. I’m sure that if Daniel Craig had murdered a busload of Girl Scouts the night before the premiere, MGM would have disposed of the corpses and paid off the families – studios move heaven and Earth to help these films succeed. The idea that Radiohead wrote the perfect Bond theme, and the studio told them “Sorry, the deadline was 5PM Eastern Time, not Pacific” does not strike me as believable.

The second – and to my mind, far more plausible – explanation is that the studio just didn’t like the song. According to Mendes, someone at the studio felt the song was “melancholy” — imagine that, a melancholy Radiohead song. Who could have seen that coming? “Radiohead” normally means “peppy, up-tempo numbers with blistering saxophone solos that teenagers can dance to.” I guess MGM expected a goofy little ditty about a hot rod filled with wacky sound effects – that’s what you expect from Radiohead. But the band submitted a moody, layered, orchestral thing; I feel that the disconnect is Radiohead’s fault for choosing this moment to depart from the kazoo-and-ukelele-based novelty songs that made them famous.

But, that was the verdict: “Too melancholy”. I don’t know if that was the feeling of one executive or many; I like to think there were 50 executives around a table, 49 loved it, and then one gave it a Larry David-esque “ehhhh”. They ended up going with “Writing’s On the Wall” by Sam Smith, which in my opinion is the second-best song called “Writing’s On the Wall” (after this one). And the movie went on to make $881 million, which is a pretty good counter argument to anyone who thinks the studio made the wrong call.

The marriage between art and commerce will probably never be happy. Artists need backers, but backers want a return on their investment, so there will always be pressure to make stuff that pleases the masses. And almost by definition, something with mass appeal can’t be ahead of its time — the only exceptions are very rare cases1 where an artist pushes a boundary at the exact moment when people say “yes, that’s what we wanted”. The good news is that even though the corporate bigwigs who care about money more than art (because that is their job) didn’t attach “Spectre” to a global movie franchise, you can still hear it — watch it on Youtube and Radiohead probably get $0.000000001 as long as you watch the Alpo ad that comes first. Art in the Internet Age is never lost, it’s just buried under 50 miles of shit. And people whose job is to find the popular stuff will probably never be good at finding the good stuff.

I’ve been thinking about this for an hour, and I can only think of five artistically groundbreaking things that were also mega-hits. Here’s my list: 1) Revolver and Sgt. Pepper by The Beatles (I’m counting those two albums as one era); 2) Early Led Zeppelin (again, counting a few albums as one era; 3) The British version of The Office; 4) The Simpsons, and 5) Monty Python, generally.

Of these, only Led Zeppelin’s early albums had instant success based on quality alone (and I debated whether they were “artistically groundbreaking” and decided that they were because Zeppelin sort of invented hard rock). The Beatles went avant-garde after they were already The Fucking Beatles, so that surely helped, and The Simpsons followed a similar path, starting as a quirky-and-popular show that started to become truly innovative around Season 3 (and eventually faded artistically but stayed on the air, so you can argue that the innovative years were ancillary to the show’s commercial success). Monty Python and The Office cleared the “mega-hit” bar not by being hits right away but by continuing to be watched over several decades, and I’m counting The Office spin offs as part of their success (both in terms of commercial success and artistic output). If you want to argue that The Office shouldn’t count because Christopher Guest already invented the mockumentary, fair enough, but I included it because it was the first in what became a genre of television.

A couple close-but-no-cigars were: Things that were extremely commercially successful but not “mega-hits” (Letterman, Conan, Pulp Fiction, OK Computer, several Coen Brothers movies), things that were mega-hits but not quite innovative enough for me to call them “artistically groundbreaking” (Dark Side of the Moon, Nevermind, Louis Armstrong’s early stuff, The Godfather, Seinfeld). And I didn’t include movies like Star Wars, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Avatar because I realized that “innovation” in movies often means “special effects innovation”, and maybe I’m splitting hairs, but I’m looking for artistic innovation more than technical. When we say “unlike anything anyone had seen before” in movies, we usually mean special effects.

I'm stunned that you didn't mention the most outrageous thing of all:

Radiohead intended, more or less, for this to be their final song. You are right about Radiohead being obsessed for years with writing a "Bond Theme" musically - "Spectre" is actually the THIRD attempt from the band, there's also the discarded "Down Is The New Up" from the IN RAINBOWS sessions. And they'd finally - near what seemed to be the natural terminus of their career - achieved the thing they'd been trying to do since they started the band: "make it" by scoring a Bond theme, their childhood goal!

Then this happened. And instead of breaking up forever after the final triumph, Radiohead has gotten their revenge by deciding to reunite and tour.

Really enjoyed this essay and the mini-essay in the footnote at the end. Per the latter, I don't think you're giving early Beatles enough credit (and I think you're giving Led Zeppelin too much credit, as much as I love them). I remember reading an interview with Stephen Hawking once, in which he was asked about his ten favorite records: they were all classical music, with the exception of the Beatles' first LP Please Please Me. He said no one had ever heard anything like it at the time. If you listen to what Buddy Holly and Elvis and Roy Orbison had created at the time, Please Please Me really is lightyears ahead.