There’s a 110 Percent Chance That Our Discomfort With Statistics Is Costing Us

DON'T explain this to me like I'm a five year-old

Reading about the tragic flood in Texas, and specifically about which alerts the National Weather Service sent and when, made me think of this passage from Nate Silver’s The Signal and the Noise:

For years, when the Weather Channel said there was a 20 percent chance of rain, it actually rained only about 5 percent of the time.

People don’t mind when a forecaster predicts rain and it turns out to be a nice day. But if it rains when it isn’t supposed to, they curse the weatherman for ruining their picnic. “If the forecast was objective, if it has zero bias in precipitation,” Bruce Rose, a former vice president for the Weather Channel, said, “we’d probably be in trouble.”

Basically: If there’s a five percent chance of rain, the Weather Channel will say there’s a 20 percent chance. And that’s because if they say “five percent,” people hear “There is no chance of rain whatsoever today. If you’re planning a picnic for the Suede Lovers of America, or hauling a bunch of sugar cubes in a pickup, today’s the day, because it won’t rain and if I’m wrong you can come to my house and kick me in the face.” The Weather Channel says “twenty percent” just so that you won’t yell at them if your sugar cube-hauling plans go awry.

There’s no doubt about it: Many people don’t really understand probability. The conversation around every baseball team is a monsoon of probability ignorance despite the fact that baseball has been a stats-based game since back when the bat was a Civil War soldier’s amputated leg. Las Vegas is a city of modern-day palaces built on the misconceptions of people who look at the grandeur and think “Uh-hilk! I’ll bet they built this by giving out big paydays to people like me!” Every multiplayer board game should be called “Who Can Most Effectively Exploit The Simpleton?” Many people understand basic concepts like uncertainty and small sample size, but a shocking number don’t, and I think that catering to the people who don’t is making it hard to get accurate information.

Consider sawdust. Watch a YouTube video about any construction process that produces sawdust — and every construction process produces sawdust — and they'll warn you: SAWDUST CAN SPONTANEOUSLY EXPLODE!!! And that’s technically true: Sawdust left in a hot, moist area can have microbial buildup that creates chemical reactions that could ignite the dust. But it’s exceedingly rare and usually happens in places with lots of dust, like sawmills. But because it could happen, we scare people into treating half a cup of sawdust like it’s an undetonated nuclear bomb. We’re simply told “sawdust can ignite”, but “can” could mean “one in a billion and only if you have an oil tanker filled with sawdust” or “if you saw one 2x4 in half in your garage but don’t clean up the dust to the standard of a virology lab, then you are 99 percent of the way to Manchester By the Sea-ing yourself.” That entire range of probabilities is hidden in the word “can”.

It happens in medicine, too. It’s hard to get a doctor to tell you anything because they assume that you’re the dumbest person alive, and they’re worried that if they say “vegetables are good for you,” you’ll shove a pumpkin up your ass and sue them for malpractice. They are constantly guarding against the black swan event, the one-in-a-billion shot, and it’s not really their fault: They could get sued back to the Stone Age if everything doesn’t go perfectly. They could also get roasted on Yelp, aka “the Karen’s lawsuit”. But extreme caution constricts communication; if I assume you’re a reasonable person, I can tell you how to make a PBJ in 20 seconds. But if I’m worried that you’re an idiot who might sue me if something goes wrong, I’ll spend an hour extolling the dangers of butter knives and warning that you will be charged with murder if any peanut residue makes it to a kid with an allergy.

This same vagueness-spurred-by-caution seems to be part of the National Weather Service’s flood warning system. Here are the warning levels (with my sassy descriptions, not theirs):

Flood Advisory: Events are imminent and situations are presently occurring. The weather isn’t bad enough for a flood warning, but…there still might be a flood. Just a li’l flood, more of a glorified puddle, and not a problem if you’re wearing capri pants. So: Yes, flood, watch out, except calm down, be prepared but no biggie, except maybe it will be, who knows, how do we even know we’re not a simulation in the mind of a robot, did you ever think about that?

Flood Watch: Game time, motherfucker! (or not) A flood might occur. Then again, it might not. I guess if you think about it, all areas could be under a flood watch at all times; “a flood may or may not occur” is always a true statement. This warning level is basically “the universe is unknowable,” but people wouldn’t like it they got a push alert that said “the universe is unknowable,” so instead, we’ll say “flood watch”.

Flood Warning: LOOK BEHIND YOU!!! A FLOOD IS HAPPENING RIGHT FUCKING NOW!!! How are you even reading this — are you holding your phone above your head and clinging to a scrap of furniture like Rose in Titanic? Anyway: This alert is confirmation that the wall of water that swept away you and everything you hold dear did, in fact, occur.

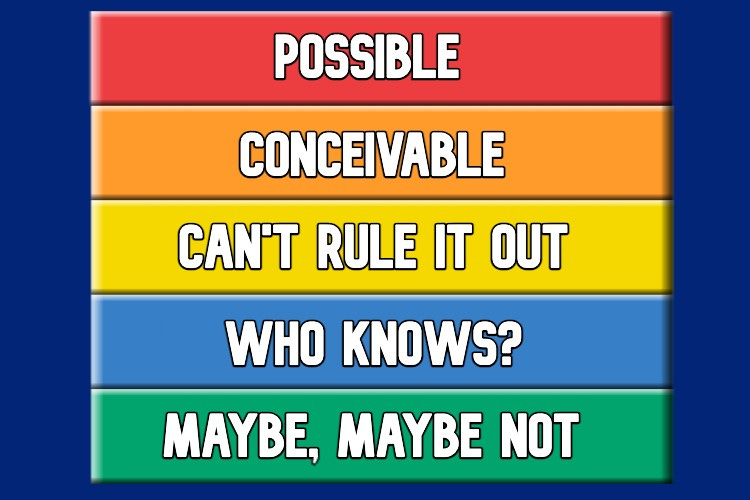

Phrased another way: Flood Advisory = no flood, Flood Watch = maybe flood, Flood Warning = yes, flood. Which means that the entire range of probabilities from .0000001% chance to 99.999999% chance is contained within “Flood Watch”. The severity of the scope also isn’t addressed — are we talking about a biblical deluge, or a tame little ankle-moistener? I don’t blame the National Weather Service — they’re doing their best, and they have to capture the fact that they know what might happen but don’t know what will happen. Nonetheless: When words like “maybe”, “can”, “could”, and “possible” encompass probabilities ranging from one in a billion to 99 out of a hundred, they’re not very useful words.

And not-very-useful warnings get ignored. I get flood alerts on my phone all the time, and I rarely pay much attention. That’s because I figure that the alert is communicating low probabilities; I interpret those warnings as “watch for standing water when you drive,” not “you are about to be deluged like Radioactive Man being washed away by a sea of acid.” Of course, if the second thing was true, the alert would look the same; the National Weather Service has boy-who-cried-wolfed itself by adopting an expansive definition of “possible”. But they also can’t reserve alerts for high-probability events, because then they’d get savaged if a low-probability event occurred.

I feel like I’d benefit from more information — I want the probabilities. I want the National Weather Service to say, for example: “We estimate a one percent probability of a minor flash flood in your area in the next three hours.” I know that they’re afraid I’ll interpret that as “go down to the creek with a bunch of priceless art and frail old people who can’t swim, it’ll be fine.” But I need that information, because without it, I’m more likely to brush off, say, a 30 percent probability of a moderate-to-severe flood. I know that the system is designed to protect against The Dumbest Person Alive, and I know that The Dumbest Person Alive will — without a doubt — yell at the authorities when they misinterpret the information. But I’m starting to think that funneling discrete events into broad words like “possible” and “could” is creating more problems than it solves.

It might be good if more people took a stats class in high school or college. It could help them navigate life, and it could help them realize that career utility infielders aren’t suddenly good just because they went 8-for-20 on a road trip. It also might make it viable for the government, doctors, and other authority figures to speak in more accurate ways. We should stop using words to express ideas that are more accurately expressed in numbers; tell me “40 percent” instead of “moderately-to-somewhat-likely-though-absolutely-not-certain”. Yes, this will confuse some people, but some people are confused by everything. That doesn’t mean that information should be withheld from people who have a shot at understanding what’s going on.

“They could also get roasted on Yelp, aka ‘the Karen’s lawsuit.’” - this subscription is worth every penny.

Maybe a compromise could be closed captioning for the innumerate.

(Yes, I am stealing this joke from Dave Barry’s “closed captioning for the humor-impaired,” which, by the way, Mauer, you could also use around here given the number of comments that fail to understand that jokes are being made).